250th Series: Chaplains and the Revolutionary War

By Chaplain General Reverand David J. Felts

SAR Magazine

Summer 2020, Vol. 115 No. 1

During wars, there is a need for “men of faith” to encourage the fighting men and exact some sort of cohesion, hope and purpose out of the chaos and destruction of war. Consider the deeds of some heroic men of faith, chaplains for all posterity to study, such as the “Four Chaplains,” aka the “Immortal Chaplains,” or the “Dorchester Chaplains.” These were four United States Army chaplains, men of faith, who gave their lives to save other civilian and military personnel as the troopship SS Dorchester sank on Feb. 3, 1943, during World War II. Some of you will remember the iconic William Christopher character, Father Mulcahy of the 4077 ‘M*A*S*H unit, from television fame. If you are a fan of old black-and-white films, there were several movies from the 1940s and ’50s that included chaplains.

Chaplains have served in times of battle since prehistoric times. Most battle records have some indication of what we would call a chaplain. Recent studies about the history of wars indicate that of the more than 3,000 years of recorded history, only 227-plus years had no record of a war of any sort. Wars are no recent invention, no matter what popular history and songs lead you to believe. Throughout time, humankind has cried, “Give peace a chance!” and “Make love, not war!”

The men who fought in the Revolutionary War needed great hope, purpose and more to win freedom for themselves and their families—freedom to own land, freedom to grow food, freedom to make laws, and freedom to worship God as they understood him. Rumblings grew in the New World with the passage of the Sugar and Currency Acts of 1764. They grew louder with the Quartering Act and the Stamp Act the next year. The Townshend Acts of 1767 added more kindling to the fire. The pastors, preachers, ministers and priests did not ignore the opportunity to apply God’s word to these choking and binding laws.

From as early as the 1750s, men of faith decried publicly, from the pulpits of America, these horrible conditions put upon them by the King of England. They carefully pointed out how the Bible, God’s word to man, did not allow the treatment they suffered in the name of the Crown and, in some cases, of the Church of England, since the King was the self-declared head of the English Church.

The cork finally blew out as the Boston Tea Party erupted, followed by the Intolerable Acts of 1774. The cry of, “No taxation without representation!” grew louder and became more public as the pulpit began to take a clear, robust and lively stance on the issues the Colonists faced. Men of faith preached openly against the growing number of intolerable and coercive laws from the Crown of Great Britain—rules that seemed to plow under the struggling Colonists of the New World.

Most of you have heard something about Revolutionary War chaplains, men who were pastors, preachers, ministers and priests who became chaplains. These were men of faith who believed and served the universe’s sovereign and almighty God through his son, Jesus Christ. These were educated men who could handle the mental and spiritual issues that other men were not trained to handle.

There were several worship styles, including Anglican, Methodist, Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Baptist, Congregational and Quaker. Jewish congregations in the New World were not silent on these issues, either. They all believed that scripture was God’s word, given for the proper instruction and salvation of humanity. For the Christian groups, there was agreement on the central beliefs of the Old and New Testament. These believers generally gravitated into two divided camps: those loyal to the Crown, and those who protested the intolerances and tyranny of the Crown.

Though their worship styles were different, the protesting men of faith grew louder and louder about how they viewed what God was saying concerning the horrible application of laws and the treatment of the Crown’s citizenry in the New World.

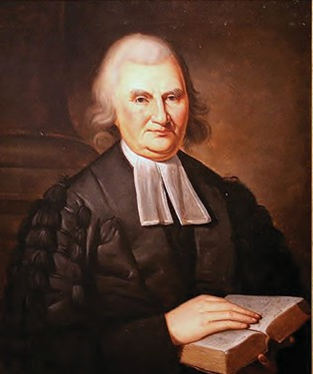

Top, Rev. Dr. John K. Witherspoon; above, “Rebel Priest” Rev. James Caldwell

When the Continental Congress convened in 1774, chaplains were called and appointed. The men who met in Congress were educated men, yet they recognized that their expertise was not in spiritual matters. They agreed to first ask for much-needed divine wisdom to react to the Intolerable Acts that had been recently passed by British Parliament, followed by the British fleet posting a blockade in the Boston harbor to prevent any outside trade on much- needed goods.

The Congressmen realized that God was in control of the universe, and they needed to ask His wisdom and direction to best handle the latest suffering placed upon them. They finally agreed to ask and appoint Rev. Jacob Duché to give “prayers,” as they called it. You have probably seen paintings of the Continental Congress, where several members were humbly on their knees while fervently praying. These men were serious. They sought a chaplain to encourage them and bring hope to their hopeless and challenging situation.

Mr. Duché was the first of many men called to serve the Continental Congress. He was followed by men who knew they should serve their country in some new way. Among them, Rev. Dr. John K. Witherspoon (New Jersey) signed the Declaration of Independence. These bold men served God first. Then, they offered their services to humankind and their government. This was something new and dangerous in the eyes of the British Crown.

These chaplains became part of a large brigade of men of faith, who took their congregations the fighting men of the Revolution. Chaplains accompanied Washington on his early journeys and military excursions and then accompanied him throughout the Revolution and into his presidency. These chaplains believed, with every fiber of their beings, that man was created by God and must learn to love God and rely on His love and care. There was minimal, if any, discrepancy on that point. They also were convinced beyond the shadow of a doubt that the Revolution was necessary and that God was leading the Colonists to the brink of making an obvious choice. It was either the British Crown, and slavery and tyranny, or it was a war for freedom, with no slavery, and with a new life with rights and privileges and meaning and hope. This war must be won.

For those who have doubts about men of faith taking part in such activity, a word of warning: These chaplains preached God’s word with all their hearts, fiber and belief, but like the prophets of old who built the wall of Jerusalem with one hand and held their sword in the other, these men of faith often had their pistols at the ready, lying on the side of the pulpit, or their musket propped against the lectern as they preached. Be assured that they did extraordinary things by the power of faith in God. They all played an essential part in making the Revolution successful.

The Rev. Dr. John K. Witherspoon was born in Scotland, the grandchild of the fiery reformer John Knox. Dr. Witherspoon preached in Scottish churches and gathered at least two militias to defend against the Crown’s forces before coming to the New World. Witherspoon arrived in Princeton, N.J., to take the presidency of the troubled 22-year-old College of New Jersey in 1768. By the time of the Revolution, the College of New Jersey’s main hall had been badly damaged and books and other equipment had been destroyed by occupying British soldiers.

Witherspoon gathered funding well beyond what was needed and donated 300 volumes from his library, and most of his scientific and medical equipment, for use by the college students. The result was that Witherspoon gave us today what we know as a liberal arts education. Later, in 1789, Dr. Witherspoon was the founding moderator of the newly formed Presbyterian Church in America.

Then, there were the Muhlenberg Brothers: Frederick was a pacifist; Peter was a hawk. One was a student of classical learning, while Peter was a soldier for the British during his education. Then came the day when the pacifist Frederick had his mind changed. He stood with British officers and witnessed them burning his church building to the ground because he was of the “wrong” religion. Frederick was a Lutheran and was not adherent to the British Anglican Church under the sermon, he tore open his clerical robes to reveal a Continental Army officer’s uniform under it. While the drums beat outside the church, men kissed their wives and families goodbye, and 30-plus men were signed up to fight.

Further north, the Rev. James Caldwell was known as the “Fighting Parson.” He served with the Continental Army in New Jersey. Caldwell stood with British officers as they burned his Presbyterian church to the ground. Around that time, Caldwell’s wife was killed by British soldiers as they shot through the window of Caldwell’s home, killing his wife as she sat on a bed, holding their child. This was a man of faith from the First Presbyterian Church of Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth), N.J. He became a chaplain to the First Army and threw himself entirely into backing the Revolution and its soldiers.

It is widely reported that Benjamin Franklin had printed a little volume of Isaac Watts’ hymns. These were published into a small volume that churches could afford and were widely spread about the eastern region churches. When Caldwell’s company ran out of musket wadding at the battle of Springfield, N.J., Caldwell ran to the nearby Presbyterian Church and carried several Isaac Watts hymnals to the troops. As he tore pages from the hymnals, he is reported to have shouted, “Now give ’em Watts, boys! Put Watts into them, boys!”

Caldwell was called the “Rebel Priest” and the “High Priest of the Rebellion” by some British. They offered a reward for his capture. After all, the British thought, this was a Presbyterian war, and Caldwell was not Anglican, but he was a rebellious Presbyterian, just like those “bloody Scots” who would not adhere to the King’s Church.

May 27, 1777, Congress finally appointed one chaplain to each brigade, with the same pay and rations as an army colonel. General Washington had to fight Congress to get these provisions for chaplains. His letters often expressed his sentiments about the necessity of having the chaplain accessible to the men and well-compensated for their work. Washington finally succeeded.

Chaplains often bore arms, and some had professional medical training, serving as surgeons, as well. One such chaplain was David Avery, who owed his conversion to the ministry of George Whitefield, a British Evangelist who visited America years earlier. After his conversion, Avery was determined to add to his medical education and become a minister. He entered Yale as a freshman in 1765, in the same class as Timothy Dwight, grandson of Jonathan Edwards. Avery was a brilliant 13-year-old who would later serve as an army chaplain.

Avery brought his own medicine and instruments to supplement what was lacking in the army’s supplies. He served at the Battle of Bunker Hill and was reported to be “intrepid and fearless in battle, unwearied in his attentions to the sick and wounded.” Avery suffered the hardships and deprivations of army life with a cheerful attitude, no doubt bolstered by his patriotism and love for his country. It was said that he was “everything Washington wanted in a chaplain.” Avery often rode with Gen. Washington and took meals with him.

Hezekiah Smith, a Baptist minister and church planter from Haverhill, Mass., traveled throughout Maine and New Hampshire. His preaching in remote locations helped establish 13 churches. A 1762 graduate of the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, Smith, and Isaac Backus, gathered funds and subscriptions to develop Rhode Island College, now Brown University.

Smith was diligent in fulfilling his duties, encouraging the soldiers and ministering to the wounded, often putting himself in danger. Although he earned the respect of Washington for the way he fulfilled his role as chaplain, he was, first and foremost, a pastor. He returned home as soon as he was released from the army to pastor his congregation in Haverhill. Smith corresponded with Washington after the war ended, and Washington visited Hezekiah in Haverhill in 1789.

Baptist minister David Jones served as a missionary to the Indian tribes of the Ohio Valley for two years. He was so outspoken about his views on the Revolutionary War that “he became obnoxious to his Tory neighbors” and was compelled to leave the Freehold Baptist Church where he served as pastor. Jones moved to Pennsylvania, to become the pastor of the Great Valley Baptist Church. It was Chaplain Jones’ custom to preach as often as possible before entering battle. He preached to the troops at Valley Forge, following the arrival of the news that France had recognized American independence. Jones served under the command of General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, from Chester County near Paoli, Penn. General Wayne earned his nickname for the bravery and fearlessness he displayed on the battlefield.

David Jones was a good fit with his commanding officer in this regard. He was so heroic on the battlefield that British Gen. Howe offered a reward for Jones’ capture, and many plots were laid to capture him. In addition to his military and chaplain’s duties, Jones served as a courier for Gen. Wayne from time to time. In a letter to Benjamin Franklin, written from Ticonderoga on July 29, 1776, Wayne writes in part, “Through the medium of my Chaplain (David Jones) I hope this will reach you as he has promised to blow out any man’s brains who will attempt to take it from him.”

Abraham Baldwin studied law at Yale and became a minister and chaplain to the soldiers in Connecticut. After being discharged from duties, he moved to Georgia and served in the Georgia legislature. While there, he founded the first state-chartered public college in the United States, the University of Georgia.

Chaplains have long been concerned with education. They were, and are, spiritually strong men who encourage and teach fighting men to handle spiritual matters. They lead their military congregations, encouraging and helping them so they can find some cohesion, hope and purpose in what they are doing in the chaos and destruction war.

Chaplains have always been men of faith. They have been men who believed in what man could not see with the naked eye, but what man could perceive with the soul; the heart. “These men remind us that there is more to life than what we see, touch, taste, or feel. They remind us that there is truth and life beyond our perception. They remind us that truth and life are eternal.” Chaplains represent to us a connection with the eternal, truth and life. They serve our hope, purpose and meaning. Chaplains have always stood for something hopeful, positive, significant and eternal.

These were “men of faith,” pulpit heroes and chaplains who believed and served the sovereign and almighty God of the Universe through his Son, Jesus Christ. These were educated men who were taught to handle the mental and spiritual issues that other men were not trained to handle. These chaplains gave their lives, and more, so that the Revolution, the freedom of America and individual freedom could finally be won. God rest them all and bless their memory to us forever.

Soli Deo Gloria. ~DJF