The Story Behind a Forgotten Symbol of the American Revolution: The Liberty Tree

By Erick Trickey

Smithsonian.com

May 19, 2016

While Boston landmarks like the Old North Church still stand, the Liberty Tree, gone for nearly 250 years, has been lost to history.

On the night of January 14, 1766, John Adams stepped into a tiny room in a Boston distillery to meet with a radical secret society. “Spent the Evening with the Sons of Liberty, at their own Apartment in Hanover Square, near the Tree of Liberty,” Adams wrote.

Over punch and wine, biscuits and cheese, and tobacco, Adams and the Sons of Liberty discussed their opposition to Britain’s hated Stamp Act, which required that American colonists pay a tax on nearly every document they created. Mortgages, deeds, contracts, court papers and shipping papers, newspapers and pamphlets – all had to be printed on paper with tax stamps.

The colonists were furious, but how to combat the Parliamentary action was a point of contention. Between Adams and his hosts, the methods differed. The future American president was resisting the tax with petitions, speeches and essays. His hosts, also known as the Loyal Nine, had threatened to lynch the king’s stampman.

Throwing off the British and creating a new nation required a mix of Adams’ approach and the Loyal Nine’s: both high-minded arguments about natural rights and angry crowds’ threats and violence. After his visit, Adams assured his diary that he heard “No plotts, no Machinations” from the Loyal Nine, just gentlemanly chat about their plans to celebrate when the Stamp Act was repealed. “I wish they mayn’t be disappointed,” Adams wrote.

Throughout these early years before the revolution, the ancient elm across from the distillery became Massachusetts’ most potent symbol of revolt. In the decade before the Revolutionary War, images of the Liberty Tree, as it became known, spread across New England and beyond: colonists christened other Liberty Trees in homage to the original.

Yet unlike Boston’s other revolutionary landmarks, such as the Old North Church and Faneuil Hall, the Liberty Tree is nearly forgotten today. Maybe that’s because the British army chopped down the tree in 1775. Or maybe it’s because the Liberty Tree symbolizes the violent, mob-uprising, tar-and-feathers side of the American Revolution – a side of our history that’s still too radical for comfort.

The tree was planted in 1646, just 16 years after Boston’s founding. Everyone traveling to and from the city by land would have passed it, as it stood along the only road out of town, Orange Street. (Boston sat on a narrow peninsula until the 1800s, when the Back Bay was filled in.) Though no measurements of the tree survive, one Bostonian described it as “a stately elm… whose lofty branches seem’d to touch the skies.”

The tree was almost 120 years old in March 1765, when the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act. After years of several other slights, including the Sugar Act’s taxes and the quartering of 10,000 British troops in North America, the colonies resisted. In Boston, opposition was led by the Loyal Nine, the band of merchants and artisans Adams encountered. The conspirators, including distillers, a painter, a printer, and a jeweler, wanted to go beyond the learned arguments about the inalienable rights of Englishmen taking place in newspapers and meeting halls. So, they staged a moment of political theater with symbols and actions anyone could understand.

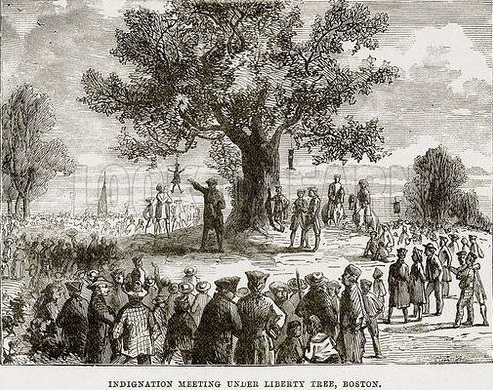

Early in the morning of August 14, Bostonians discovered the effigy hanging from the tree. Initials pinned to the effigy, “A.O.,” identified it as Andrew Oliver, the Boston merchant who had agreed to collect the stamp tax. Next to him dangled a boot, a reference to Lord Bute, the former British prime minister whom many colonists blamed for the act. A small devil figure peeked up from inside the boot, holding a copy of the law. “What Greater Joy did ever New England see,” read a sign that hanged from one of the effigy’s arms, “Than a Stampman hanging on a Tree!”

Hundreds of Bostonians gathered under the elm, and a sort of party atmosphere broke out. “Not a Peasant was suffered to pass down to the Market, let him have what he would for Sale, ’till he had stopp’d and got his Article stamped by the Effigy,” the Boston Gazette reported. The sheriff came to cut down the effigy, but the crowd wouldn’t let him.

At 5 p.m. that day, shoemaker Ebenezer McIntosh – known for leading the South End’s brawlers in the annual anti-Catholic Pope’s Day riots – led several protesters as they put the effigy in a coffin and paraded it through Boston’s streets. “Liberty, property, and no stamps!” cheered the crowd of several hundred as they passed a meeting of Massachusetts’ governor and council at the Town House (now the Old State House). On the docks, some of the crowd found a battering ram and destroyed a building that Oliver had recently constructed. Others gathered outside Oliver’s house. “They beheaded the Effigy; and broke all the Windows next [to] the Street,” wrote Francis Bernard, the horrified governor of Massachusetts, “[then] burnt the Effigy in a Bonfire made of the Timber they had pulled down from the Building.” The mob also stormed into the house, splintered furniture, broke a giant mirror, and raided Oliver’s liquor supply. Oliver, who had fled just in time, sent word the next day that he would resign as stamp commissioner.

The Loyal Nine had teamed up with McIntosh because of his skills in turning out a crowd. But after he led a similar attack on Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s house on August 26, they decided he’d gone too far. A town meeting at Faneuil Hall voted unanimously to denounce the violence. Going for a more lofty symbolism, the Loyal Nine attached a copper plate to the elm a few weeks later. “Tree of Liberty,” it read.

The tree’s potency as rally site and symbol grew. Protesters posted calls to action on its trunk. Towns in New England and beyond named their own liberty trees: Providence and Newport, Rhode Island; Norwich, Connecticut; Annapolis, Maryland; Charleston, South Carolina. Paul Revere included the Liberty Tree, effigy and all, in his engraved political cartoon about the events of 1765.

When news of the Stamp Act’s repeal reached Boston in March the following year, crowds gathered at the Liberty Tree to celebrate. The bell of a church close to the tree rang, and Bostonians hanged flags and streamers from the tree. As evening came, they fastened lanterns to its branches: 45 the first night, 108 the next night, then as many as the tree’s branches could hold.

For a decade, as tensions between the colonies and Britain grew, Boston’s rowdiest, angriest demonstrations took place at the Liberty Tree. “This tree,” complained loyalist Peter Oliver (Andrew Oliver’s brother), “was consecrated for an Idol for the Mob to Worship.” In 1768, the Liberty riot, a protest over the seizure of John Hancock’s ship, ended when the crowd seized a customs commissioner’s boat, dragged it from the dock to the Liberty Tree, condemned it at a mock trial there, then burned it on Boston Common. In 1770, a funeral procession for Boston Massacre victims included a turn past the tree. In 1774, angry colonists tarred and feathered Captain John Malcom, a British customs official, for caning a shoemaker, then took him to the Liberty Tree, where they put a noose around his neck and threatened to hang him unless he cursed the governor. (He didn’t, and they didn’t.)

For freemen like brothers agree,

With one spirit endued, they one friendship pursued,

And their temple was Liberty Tree…

In 1775, after war broke out, Thomas Paine celebrated the Liberty Tree in a poem published in the Pennsylvania Gazette, celebrating its importance to all Americans, including the common man:

Finally, in August of that year, four months after Lexington and Concord, British troops and loyalists axed the tree down. (It reportedly made for 14 cords of firewood — about 1,800 cubic feet.)

After the British evacuated Boston on March 17, 1776, revolutionary Bostonians tried to reclaim the site. They erected a “liberty pole” there on August 14, the 11th anniversary of the first protest. In the years to come, Boston newspapers occasionally mentioned the site of the Liberty Stump. But it didn’t last as a landmark — even though the Marquis de Lafayette included it in his 1825 tour of Boston. “The world should never forget the spot where once stood Liberty Tree, so famous in your annals,” Lafayette declared.

Thomas Jefferson did the most to make the Liberty Tree a lasting metaphor, with his 1787 letter that declared, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants.” Since then, Boston and the world have done a spotty job of following Lafayette’s advice.

Today, the spot where the Liberty Tree stood, at Washington and Essex streets in Boston, is marked by a bronze plaque lying at ground level in an underwhelming brick plaza. Across the street, an 1850s wooden carving of the tree still adorns a building. The site was left out of Boston’s Freedom Trail. Historian Alfred F. Young thought that wasn’t an accident. “[Boston’s] Brahmin elite fostered a willful forgetting of the radical side of the Revolution,” he argued in his 2006 book Liberty Tree: Ordinary People and the American Revolution. It’s one thing, in this telling, to celebrate the Battle of Bunker Hill and let the Boston Tea Party symbolize revolutionary mischief, another thing to celebrate mobs who threatened hangings, ransacked houses, tarred and feathered. A 23-foot-tall silver aluminum Liberty Tree, created for the 1964 World’s Fair, later moved to Boston Common, where it failed miserably to become a landmark; in 1969, Boston officials scrambled to find a new home for the widely despised eyesore with little-to-no historical context. There is, however, a democratic argument for remembering the Liberty Tree. “The Revolution has a different meaning if you start here,” Nathaniel Sheidley, director of public history at the Bostonian Society, told the Boston Globe in 2015. “It wasn’t all about guys in white wigs.”

Today, Boston’s Old State House museum displays part of the flag that flew above the Liberty Tree. It also houses one of the lanterns that decorated the tree at the Stamp Act repeal celebration on March 19, 1766 — 250 years ago this month. Last August 14, on the 250th anniversary of the Liberty Tree’s first protest, several history and activist groups gathered at Washington and Essex, carrying lanterns. And next year, the city of Boston hopes to start construction of an upgraded Liberty Tree Park at the site – and plant a new elm there.