250th Series: Medicine in the Time of the Revolution

By John Turley, MD, WVSSAR

SAR Magazine

Fall 2020, Vol. 115, No. 2

We all have an idea of what life was like for our Revolutionary ancestors: no electricity, running water, indoor plumbing, central heat, telephones, computers, nor rapid transportation. But try to imagine what medicine was like under those conditions. Most things we take for granted as a routine part of our medical care did not yet exist. There were no X-rays, lab tests, EKGs, antibiotics and no concept of sterile procedure or anesthesia. Surgery was a painful and often fatal process.

In many ways, medicine was more of a trade than a profession. There were only two medical schools in 18th-century America. The Philadelphia Medical College was founded in 1765, and Kings College Medical College in New York was established two years later. Most physicians and surgeons (“chirurgiens,” as it was spelled at the time) who had formal training received it in Europe. By far, most physicians received their training from a one- to three-year apprenticeship in the office of an established physician.

Others, particularly on the frontier, simply declared themselves physicians and set up practice. In some remote areas, surgery was performed by the local barber or butcher because they had the tools.

The first medical society was formed in Boston in 1735. By the mid-1700s, most Colonies required a medical license of some form. In many Colonies, the medical license was little more than a business tax, with few, if any, enforceable professional standards. The first hospital in the Colonies was founded in Philadelphia in 1751 by a group that included Benjamin Franklyn.

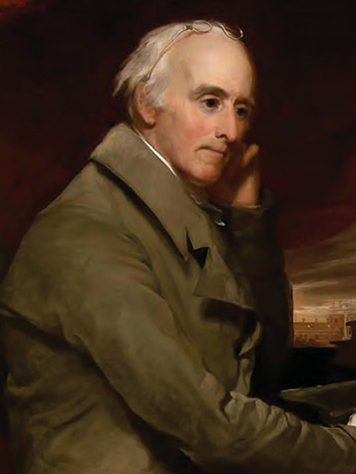

Noted physician, civic leader and educator Benjamin Rush.

In 1775, there were an estimated 3,000 physicians practicing in the Colonies. Fewer than 300 had a medical degree or a certificate from a formal apprenticeship. Early attempts at licensing were resisted in an effort to place a monopoly on medicine. Massachusetts was the first Colony to attempt regulation by issuing a certificate of proficiency for completion of an approved apprenticeship. But even in Massachusetts, as notable a physician as Benjamin Rush reported that the only prerequisite for “a doctor’s boy [apprentice] is the ability to stand the sight of blood.”

While modern concepts of disease and sanitation were beginning to almost 1,000-year-old ideas of the Greek physician Galan. He believed that the body had four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Good health required a balance of the humors, and illness resulted from their imbalance. Attempts to restore balance included bleeding, purging, diuretics and laxatives, and placing heated cups on the back to form blisters and draw out the humors. It was this belief that led to the bleeding that hastened George Washington’s death. Quite literally, the cure was worse than the disease.

The physicians of the time had few effective medicines and often acted as their own apothecary, compounding medications of spices, herbs, flowers, bark, mercury, alcohol or tar. Opium elixir was marketed to help babies sleep through the night. Mercury was used to treat everything from syphilis to scabies. Voltaire summed up the state of pharmacology when he said that “a physician is one who pours drugs of which he knows little into a body of which he knows less.”

Disease and hardship were a fact of life in the Colonies. One in eight women died in childbirth or from complications of pregnancy. One in 10 children died before the age of 5. Diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, typhus and measles ravaged many communities. These were especially deadly for Native Americans.

Smallpox was perhaps the deadliest disease of the Colonial Period. Entire American Indian tribes were annihilated. Epidemics repeatedly swept through the Colonies in the 1700s, killing thousands. George III became king of England in part because of smallpox; the last Stewart claimant to the throne died of the disease, and England looked to the House of Hanover for the German-born King George I.

Inoculations against smallpox had been widespread in Africa and in Arab countries for many years. In the American Colonies, inoculation was denounced as barbaric, and some clergy preached that it was thwarting God’s will. Despite the support of such notables as Cotton Mather and Benjamin Franklin, inoculation against the disease was not widespread until George Washington, seeing the debilitating effect of smallpox on the Continental Army, ordered the mass inoculation of all troops.

Bleeding, a common medical practice in the 18th century, hastened the death of George Washington.

Disease and poor hygiene were the greatest foes faced by the Army. John Adams reported that for every evolve in the late 18th century, many practitioners still subscribed to the soldier killed in battle, 10 died from disease. On July 25, 1775, the Continental Army Medical Corps was formed. It was called the Hospital, not to be confused with buildings of the same name. Initially, each regiment was required to provide its own surgeon, and there were no established qualifications. Only Massachusetts required examination of regimental surgeons, and many Colonies did not provide the surgeons with a military rank. To make matters worse, the first director general of the Army Medical Corps, Dr. Benjamin Church, was a British spy.

Modern ideas of sanitation were unknown to most Colonists. Few people bathed, believing it removed the body’s protective coating. Most soldiers had only a single set of clothes, in which they also slept and which they almost never washed. Army camps were hot beds of flux (dysentery) and camp fever (typhoid and typhus; the distinction between them was unknown). Camp fever took a huge toll on the army because it left the survivors so debilitated that they required almost constant care and seldom returned to duty.

Sanitation consumed a large part of Gen. Washington’s attention at Valley Forge. Daily inspections of latrines, garbage disposal and animal manure consumed many hours. Attempts to prevent and treat the itch (scabies) were constant. At times, several hundred soldiers could be unfit for duty due to infestation. What little clothing and blankets they did have often had to be burned to prevent the spread of scabies.

Conditions in army hospitals were not much better and were sometimes far worse. Camp fever spread rapidly through the close confines, often killing entire wards, including the staff. Death rates could run as high as 25 percent in hospitals, and many soldiers preferred to remain in camp, where they felt they had a better chance of survival. Dr. Benjamin Rush stated, “Hospitals are the sinks of human life. They robbed the United States of more citizens than the sword.”

The French, as with many things during the Revolution, aided the Patriots in their health problems. Dr. Jean Francois Coste, chief medical officer of the French Expeditionary Force, was one of the first to introduce strict regulations concerning sanitation and hygiene in army camps. The Americans, noting the significantly better health of their allies, were quick to follow suit.

The Revolution was always close to failure. It was made even closer by widespread disease. But as with everything, our Patriot Ancestors persisted and triumphed.

About the Author

Compatriot John Turley is the Secretary Treasurer of the West Virginia Society. He has practiced both emergency medicine and family medicine and was a U.S. Navy hospital corpsman in Vietnam from 1969-70 and a Marine Corps infantry officer from 1974-80.

Sources

- Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Medicine in Colonial Massachusetts 1620-1820. Boston, MA, 1980.

- Miller, Christine. A Guide to 18th Century Military Medicine in Colonial America. Lexington, KY, 2016.

- Reiss, Oscar, MD. Medicine and the American Revolution: How Diseases and their Treatments Affected the Colonial Army. McFarland & Co, Jefferson, NC, 1998.

- Shryock, Richard. Medicine and Society in America 1660–1860. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1960.

- Terkel, Susan. Colonial American Medicine. Franklin Watts, NY, 1993.

- Wilbur, C. Keith, MD. Revolutionary Medicine 1700 -1800. The Globe Pequot Press, Guilford CN, 1980.