Chaplains and the Revolutionary War By Chaplain General Reverand David J. Felts SAR Magazine Summer…

Andres Cragie: Life of a Massachusetts patriot and scoundrel

First Apothecary General of the Continental Army

By Anthony J. Connors

Harvard Magazine

November-December 2011

After serving as the first Apothecary General of the Continental Army during the American Revolution, Andrew Craigie made a fortune in land and securities speculation in New York. Returning to his native Massachusetts, he purchased one of the most elegant homes in Cambridge, built the bridge connecting Boston to Lechmere Point, and developed East Cambridge. Yet years before his death, Craigie had become a ghostly figure, self-confined to his mansion to avoid arrest. Cambridge boys, including future physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, would knock on his shuttered windows and then run, as if from a haunted house. How had “Doctor” Craigie fallen so low?

After serving as the first Apothecary General of the Continental Army during the American Revolution, Andrew Craigie made a fortune in land and securities speculation in New York. Returning to his native Massachusetts, he purchased one of the most elegant homes in Cambridge, built the bridge connecting Boston to Lechmere Point, and developed East Cambridge. Yet years before his death, Craigie had become a ghostly figure, self-confined to his mansion to avoid arrest. Cambridge boys, including future physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, would knock on his shuttered windows and then run, as if from a haunted house. How had “Doctor” Craigie fallen so low?

The son of a Scottish ship captain and his Nantucket wife, Craigie attended Boston Latin, and by April 1775 had gained sufficient pharmaceutical experience to be appointed apothecary of the Massachusetts army. After tending the wounded at Bunker Hill, he was introduced to Samuel Adams as “a very clever fellow,” and his name came to the attention of General George Washington; he was commissioned Apothecary General in 1777. For the duration of the war he traveled widely to obtain medical supplies for the army and produced the medicine chests used to treat sick and wounded soldiers at Valley Forge and elsewhere. His loyalty was recognized by Washington, although they never met.

The revolutionary cause was good for Craigie, providing business connections in the pharmaceutical trade. But even before the war ended, he had set his sights higher: a Boston Latin classmate asked in 1782 whether he had “a mind to speculate?” He did, and was soon among the growing circle of financiers and speculators surrounding Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Craigie engaged in legitimate transactions, but also partnered with the nefarious William Duer, a Hamilton assistant. In one particularly egregious case, Duer illegally directed Treasury business to Craigie in exchange for an $8,000 bribe. The men in Hamilton’s circle had insider knowledge of his plan for the new federal government to assume the war debts of the states, thereby making state debt certificates a better bet. Craigie bought up large amounts of discounted South Carolina paper and made a tidy profit.

This was the sort of cozy insider relationship that Hadton’s critics Jefferson and Madison warned would concentrate the nation’s wealth in the hands of a few powerful speculators. Exhibiting no such qualms, Craigie brashly wrote that his speculative strategy was to associate with “people who from their official situation know all the present & can aid future arrangements either for or against the funds.” Many congressmen were also up to their ears in insider deals: Congress delayed acting on Hamilton’s financial plan, Craigie observed, “because their private arrangements are not in readiness for speculation.” He had so insinuated himself with legislators that one of his partners quipped, “Should a bill of sale be given of Congress, Andrew would certainly pass as appurtenant.”

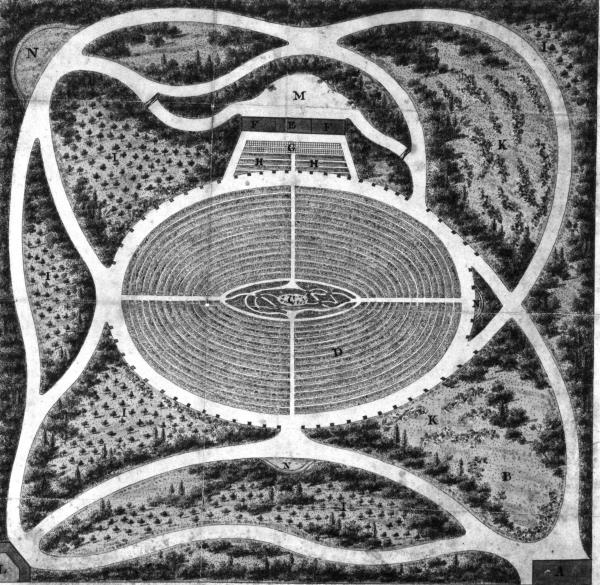

Craigie also played a part in Duer’s audacious deal to purchase and resell five million acres of Ohio land. But by the time that fiasco landed Duer in debtor’s prison, Craige had moved to Cambridge where, early in 1791, he purchased the Brattle Street mansion that had served as Washington’s headquarters during the siege of Boston. After renovating it into a “princely bachelor’s establishment: he looked for a suitable wife. Although described as “a huge man, heavy and dull,” he had money, connections, and big plans, enough to win the hand of Elizabeth Shaw of Nantucket. The marriage was soon blighted, it was said, by her receiving letters from a former suitor – and Craigie had his own secret: an Illegitimate daughter. Nevertheless, their house became a center of society, with a dozen servants, a well-stocked wine cellar, and sumptuous parties, especially during Commencement season. Queen Victoria’s father and the French diplomat Talleyrand were guests. The couple cemented their Harvard connection by donating portraits of George Washington and John Adams by John Trumbull, and three acres of land for the Harvard Botanic Garden.

Craigie’s development of East Cambridge left an indelible mark. With partners, he secretly bought up 300 acres around Lechmere Point: farms and marshland became a vibrant residential and industrial area, especially after Craigie persuaded Middlesex County authorities to relocate the county court from Harvard Square to a new Charles Bulfinch building in East Cambridge. In 1809, he and his associates completed construction of Craigie Bridge, connecting Cambridge to Boston. His rerouting of roads to steer traffic toward his toll bridge did not enhance his popularity.

The result of all this speculation and extravagant living was a greatly overextended empire. Unable to pay his many creditors, Craigie confined himself to his Cambridge estate to dodge debtor’s prison. After he died of a stroke, his wife was forced to rent rooms to Harvard faculty members, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who later owned the house. (It became the Longfellow National Historic Site.) Craigie Bridge now props up the Museum of Science and Craigie’s Pond, once a favorite skating spot, has been drained. Locally, only Craigie Street recalls this paradoxical character from the earliest years of the American Republic. But his patriotic service is still recognized as an outstanding federal government pharmacist each year receives the Andrew Craigie Award.

Source: Harvard Magazine, November-December 2011. Independent historian Anthony J. Connors, A.L.M.’93, most recently edited Volume One of the documentary encyclopedia “Conflicts in American History”.