The American Spy: Winning the War from the Shadows

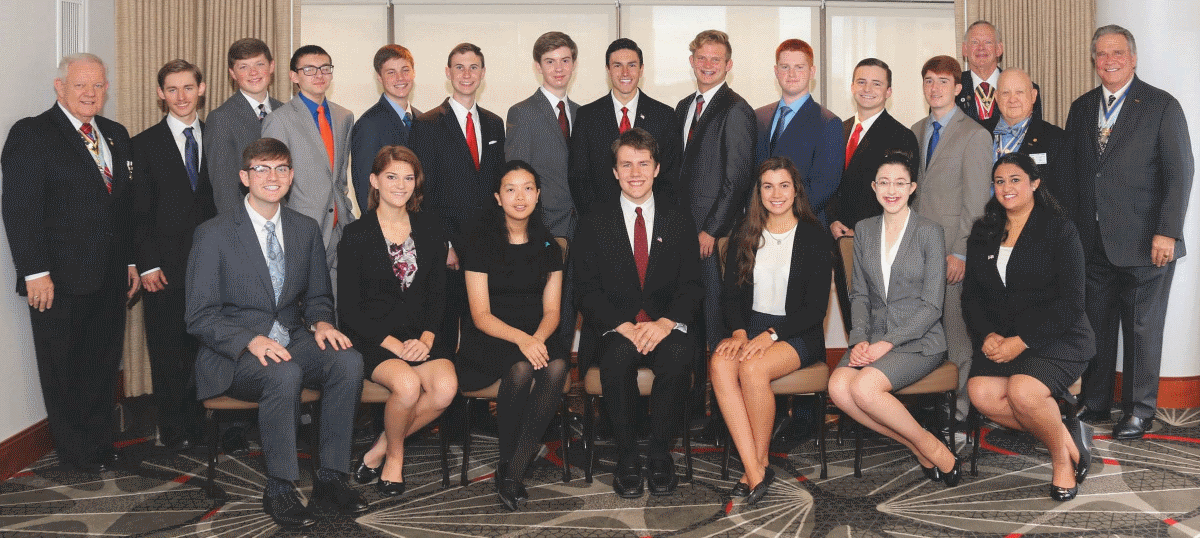

Youth Contestants at Congress 2016: Front row, from left, Luke Thomas Kirk, Louisiana; Ahnna Marie Skelly, Tennessee; Florina Lam, Maryland; Jack Ross-Pilkinton, New York; Alexandria Patricia Rodriguez, Virginia (finalist); Talia S. Fradkin, Florida; Meenal Manish Joshi, Georgia; second row, Chairman Larry McKinley; Holden B. Doane, Indiana; Caleb Scott Sayers, Mississippi; Samuel Ryan Day, Kansas; Matthew Stanley, Alabama; Liam Patrick O’Connor, Delaware (winner); Sebastian Vishnevsky Williams, Ohio; Joseph L. Cozzi, Illinois (finalist); Harrison Middleton, California; William David Rhor, Kentucky; Corban Sorrells, Texas; Jacob Homan, South Carolina; Committee Co-Chairmen Gerald P. Brent and John H. Franklin; and President General Thomas E. Lawrence.

By Liam Patrick O’Connor

Winner, Youth Oration Contest

SAR Magazine, Vol. 111 No. 1

In the middle of a dark night, a lone rowboat crosses the Long Island Sound. The date is Sept. 12, 1776. A few weeks prior, the British army, under the command of Gen. William Howe, had successfully invaded Long Island. George Washington, in defeat, retreated to Manhattan. He was desperate to gain any bit of intelligence on the British army’s next plan of attack. One young man in this boat, by the name of Nathan Hale, had volunteered to travel behind enemy lines as a spy.

As the boat landed, Hale was dressed in civilian clothing so that he could operate under the guise of a schoolteacher. In the following days, he began to collect intelligence; however, his service was cut short. Stories vary as to how his identity was discovered, but it is known that Hale was marched to the gallows on Sept. 22, 1776. Before he was hanged, he uttered the now famous line, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” In the aftermath of this espionage failure, the Continental Army improved its intelligence capabilities so as to better protect its spies and more effectively deliver sensitive information; a number of these developments continued to have a great impact on American spying practices to the present day.

Over the next few years, George Washington increased the number of people spying for the army. His greatest espionage achievement was the establishment of the Culper Ring: an elaborate military spy organization operating in New York City during British occupation. Its goal was to inform Washington of British troop movements in that region. To maintain secrecy, important names were given coded numbers. New York, for example, was 727, while Washington was 711.

The most successful spy in the Ring was agent 723, better known as Robert Townsend. During his service, Townsend uncovered a British plot to flood the American economy with counterfeit dollars and warned the army of a high-ranking spy in its midst, later determined to be Benedict Arnold. Another major feat involved telling Washington of an impending British attack upon the French fleet landing in Rhode Island. Because of this information, Washington maneuvered his army as to trick the British into believing that he would invade New York City, thus thwarting the British plan. Townsend did all of this without compromising his own identity; in fact historians did not discover agent 723’s real name until 1930.

From left, finalist Alexandra Patricia Rodriguez of Virginia, winner Liam

Patrick O’Connor of Delaware, and finalist Joseph L. Cozzi of Illinois.

One feature that made American espionage so effective was its vigorous utilization of cutting- edge tactics. The Revolutionary War was one of the first conflicts to use dead drops: secret containers left behind by spies to pass along information. Charles Dumas, a Dutch agent for the Americans in Europe, created the world’s first diplomatic cipher to communicate with Benjamin Franklin and the Continental Congress. Other agents, most notably in the Culper Ring, published coded messages overtly in public newspapers. Still, diplomat Silas Deane invented a heat- developing invisible ink. Later this was modified so that a sender used one chemical to write a message invisibly, while a receiver used a second British had done with Nathan Hale, the Soviets participated in a spy exchange with the U.S., another practice that was pioneered in the Revolutionary War. Later this was modified so that a sender used one chemical to reveal it; this was called a “sympathetic stain.” Washington instructed his spies to, “write a letter in the Tory stile with some mixture of family matters and between the lines … communicate with the Stain the intended intelligence.”

Occasionally, the British captured some of these letters and discovered the information. To counter that, Washington allowed the British to capture couriers with false documents. This type of deception tricked British generals on multiple occasions, including Gen. Cornwallis before the Battle of Yorktown.

Espionage continued to have an integral role in American military operations following the Revolutionary War. More than 150 years later, the United States was again at odds with another world power, the Soviet Union. During the Cold War, American agents used many of the same espionage methods developed during the Revolution, including ciphers, dead drops, secret inks and code names. When American spy Francis Gary Powers was captured behind enemy lines, rather than executing him as the British had done with Nathan Hale, the Soviets participated in a spy exchange with the U.S., another practice that was pioneered in the Revolutionary War.

Today, America is losing ground in the world of intelligence. Our country’s enemies are not always apparent. Hackers, such as Julian Assange, reveal secret diplomatic knowledge; turncoats, like Edward Snowden, expose classified military documents; and terrorist groups evade the Central Intelligence Agency’s information collecting technologies. Intelligence is crucial in the War on Terror. If America is to remain a dominant power in the modern world, it must learn a lesson from George Washington himself and strengthen its foreign intelligence operations. Although spies do not receive the same credit as soldiers in effecting the outcome of the Revolutionary War, or any American war for that matter, their toil, courage and patriotism were just as important.

Spies: they fought the wars from the shadows.